About

Sven Lukin

Branches

06.11.25 → 20.12.25

Sven Lukin: A Legend and an Enigma in the Art World

In the 1960s, the artist Sven Lukin, a major figure of the New York avant-garde, became one of the fathers of the Shaped Canvas.

After immigrating from Latvia in 1949, Lukin received his BFA at the University of

Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where he was taught by the architect Louis Kahn, who

remained one of his mentors. Lukin first exhibited at the Betty Parsons Gallery (1961), then at the Martha Jackson Gallery (1962), before being represented exclusively by Pace Gallery, where he had four solo exhibitions from 1963 until 1972, the year he decided to withdraw from the art scene. From that point on, he refused to exhibit his work at commercial galleries, all the while continuing a more intimate artistic practice.

Lukin’s best-known works date from the 1960s—minimalist paintings in relief,

and abstract, colored canvases in three dimensions. These works go nearly to the point

of invading space and architecture, like Lukin’s undulating wall, over 36 meters long, in

green, pink, and orange—a permanent installation at the Empire State Plaza in Albany,

and still the artist’s most iconic piece.

Sven Lukin: A Legend and an Enigma in the Art World

In the 1960s, the artist Sven Lukin, a major figure of the New York avant-garde, became one of the fathers of the Shaped Canvas.

After immigrating from Latvia in 1949, Lukin received his BFA at the University of

Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where he was taught by the architect Louis Kahn, who

remained one of his mentors. Lukin first exhibited at the Betty Parsons Gallery (1961), then at the Martha Jackson Gallery (1962), before being represented exclusively by Pace Gallery, where he had four solo exhibitions from 1963 until 1972, the year he decided to withdraw from the art scene. From that point on, he refused to exhibit his work at commercial galleries, all the while continuing a more intimate artistic practice.

Lukin’s best-known works date from the 1960s—minimalist paintings in relief,

and abstract, colored canvases in three dimensions. These works go nearly to the point

of invading space and architecture, like Lukin’s undulating wall, over 36 meters long, in

green, pink, and orange—a permanent installation at the Empire State Plaza in Albany,

and still the artist’s most iconic piece.

The 50 years that have passed since Lukin’s retreat from the art world explain

why enigma, mystery, even legend, cling to his career today. Only a small group of

enthusiasts now study Lukin, whose works, so celebrated in the 1960s, have fallen into

near-oblivion. I am one of those enthusiasts. For several years, I’ve been fascinated by Sven’s work. Andy Robertson, a young artist who is Sven’s occasional assistant, introduced me to Ronald Winston, a longtime friend, collector, and protector of Sven’s. It was through them that I finally met him; my sincere thanks to both men.

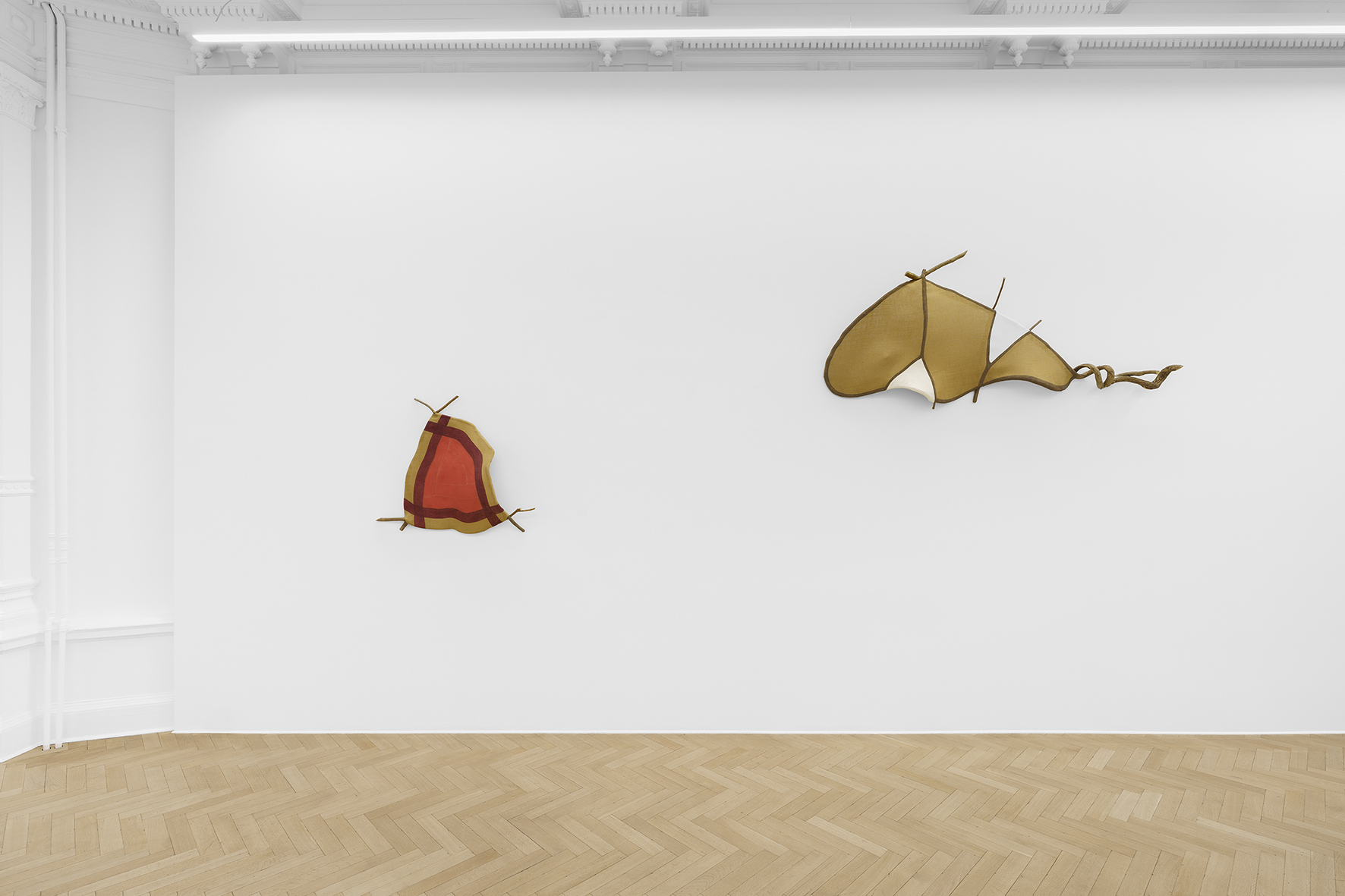

Sven Lukin has lived and worked in the same studio since 1960. When I visited

his studio, I only anticipated finally meeting one of my artistic heroes. But wandering the capharnaum of his rooms, where objects have accumulated over the course of 50

years, I noticed here and there, hung high on the walls, about 20 singular works that

immediately fascinated me. They were more of Lukin’s Shaped Canvases, but their

frames were made of slim tree branches, over which jute canvases had been

stretched—some raw, others painted with geometric motifs.

These works suggest a practice which is radically different from that of Lukin’s

1960s pieces. Even so, the underlying preoccupations are the same: the relationship

between painted elements and the shape of the support; the bands of color that trace

curves in space; and finally the omnipresent exchange between sculpture and painting.

What differs between these two periods is clearly the explicit presence of nature;

a sort of “devolution” of his 1960s work. Sven Lukin turned away from the pop-

modernist dream of that era to move towards an art that is more archaic and ritual.

Sven is mysterious and sparing when discussing his work. He gives us only an

idea of the period in which his mural-sculptures were created, in the 1990s. These

irregular polygonal forms, stretched on branches, borrow from the natural world. The

works are evocative of American Indian art and modernist abstraction, but also, Sven

says, of the shamanistic tradition of his Latvian grandfather.