About

Dana Frankfort

08.02.08 → 21.03.08

Dana Frankfort makes gestural paintings based upon the shape and connoted meaning of a specific word or phrase. These works, at times, appear to be abstract, invoking the pictorial language of such Color Field painters as Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland. However, the very literalness of the depicted language in Frankfort's paintings ground her work in a figural realism that is similar in spirit to Jasper Johns' flags or targets. Although Frankfort employs language primarily for formal reasons, it is impossible to ignore the implicit meanings in the words she selects. This creates a compelling interaction between form and content as the words give the work an internal structure in which she can play with such tensions as foreground and background and pictorial edges and compositional scale.

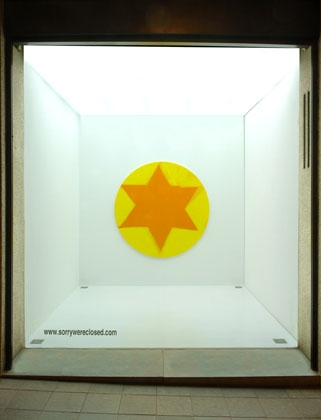

Recently, Frankfort has expanded her imagery to include representations of the Star of David. As with her pictures of words the image in these new works is subtle. The strokes that make up the star, at times, dissolve into the background.

Nevertheless, she gives the viewer enough information to recognize the symbol, which in her handling is both ambiguous and highly specific. The Star of David paintings along with the other pieces in 'DF' raise fundamental questions at the core of painting: when is a work finished, what is the relationship between pictorial edges and the picture plane, and whether or not a painting is an object.

Dana Frankfort was born in Houston, Texas. She received her MFA from Yale University and was a Core Fellow at the Glassell School of Art in Houston, Texas. She most recently had a solo show at Kantor/Feuer Gallery in Los Angeles. She will participate in the upcoming exhibition 'Abstract America' at the Saatchi Gallery in London.

NOTE TO SELF : On A Few of the Paintings of Dana Frankfort

Clear, concise, and never more than a few words long, these paintings nevertheless remain open to multiple, though not infinite, interpretations. Take for example the painting "Cute And Useless": Is it the object (a painting), the artist (a woman), or the gesture (Duchampian) that is "cute and useless"? It is easily conceivable that the correct answer is all three.

"Space Between Paintings" like Cute And Useless both minimizes itself (as in "It is merely the...") and creates a spectacle of it's own self deprecation. Created in several sizes the space between the paintings could be large or small. And of course the best and most important paintings require as much space as possible, resulting in the deployment of ever-larger (louder) signifiers of this space. And so the existence of Space Between Paintings as an object has a kind of nagging tone. Trying to push its way through a crowd of "real" paintings, it is almost insufferably annoying and steadfastly refuses to allow the "real" paintings to go about their work, presumably the recording of historical moments or sweeping canonical redefinitions of "beauty".

There is a strict materialism being enacted here, in the sense that these paintings and their messages, though existential, are far from metaphysical. It would be difficult to drastically misinterpret a painting by Dana Frankfort. It seems unlikely that meaning would stray very far from the artist's intentions. They are paintings made for a select group of like-minded individuals whose thinking is in accordance with that of the artist. After all, once you explain a joke, it is no longer funny. The banality of the messages that are scrawled is directed toward an audience whose values lie not in the hermetic contemplation of the void, but in the concrete reality of the everyday. These paintings exist in a moral universe that requires a minimum of faith on the part of the viewer. Here, one does not have to be a believer to stand with the artist as an equal before the work.

They are not mysterious. What might at first be mistaken for earnest expressionism with all of the transcendental baggage that that way of painting carries is actually something far simpler: economy. The quickest way to write a message as large as it needs to be. In looking at these paintings I am reminded of a proposition from "Rules For Selecting Art College Professors" by Otto Muehl: Whoever paints all of a 10m x 10m canvas the fastest, using their tongue as a brush, receives 15 points.

— Justin Lieberman, artist